China’s multi-dimensional warfare strategy against India has taken a concerning turn, as highlighted during the recent Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) meeting. Notably, China failed to mention the Pahalgam massacre in the joint declaration, which reflects its erratic behavior that has crossed limits in various areas.

For the past four to five years, China has imposed restrictions on supplies of specialty fertilizers to India, culminating in a complete halt of shipments. India relies on China for 80% of its fertilizer imports.

Additionally, the tunnel boring machines (TBMs) for the Mumbai-Ahmedabad bullet train project, manufactured in China by the German company Herrenknecht, are currently stuck at Chinese ports. Despite having made the payment for these machines, they have not received export clearance.

The most significant threat, however, is China’s dominance in the rare earth elements sector. Since April 2025, China has effectively halted shipments of rare earth magnets to India. These magnets are crucial for producing electric vehicles, wind turbines, and various electronic devices. Indian manufacturers are concerned that production could be disrupted if supplies do not resume soon. China plays a dominant role in the global rare earth supply chain, accounting for approximately 70% of global mining and 90% of refining capacity.

What Are Rare Earth Elements

Rare earth elements (REEs) comprise a group of 17 minerals that are crucial for advanced technologies, particularly in military weapon systems. Despite their name, most REEs are not actually rare. They are called “rare” because they are evenly distributed across the Earth rather than being concentrated in specific locations. Promethium is the only rare earth element that is scarcer than silver, gold, and platinum. The other two least abundant REEs, thulium and lutetium, are nearly 200 times more common than gold.

REEs are typically found in unusual rock types and uncommon minerals. Compared to common base and precious metals, rare earth elements are less likely to be concentrated in commercially exploitable ore deposits. As a result, the majority of rare earths are sourced from a limited number of locations.

Why Do We Need REEs

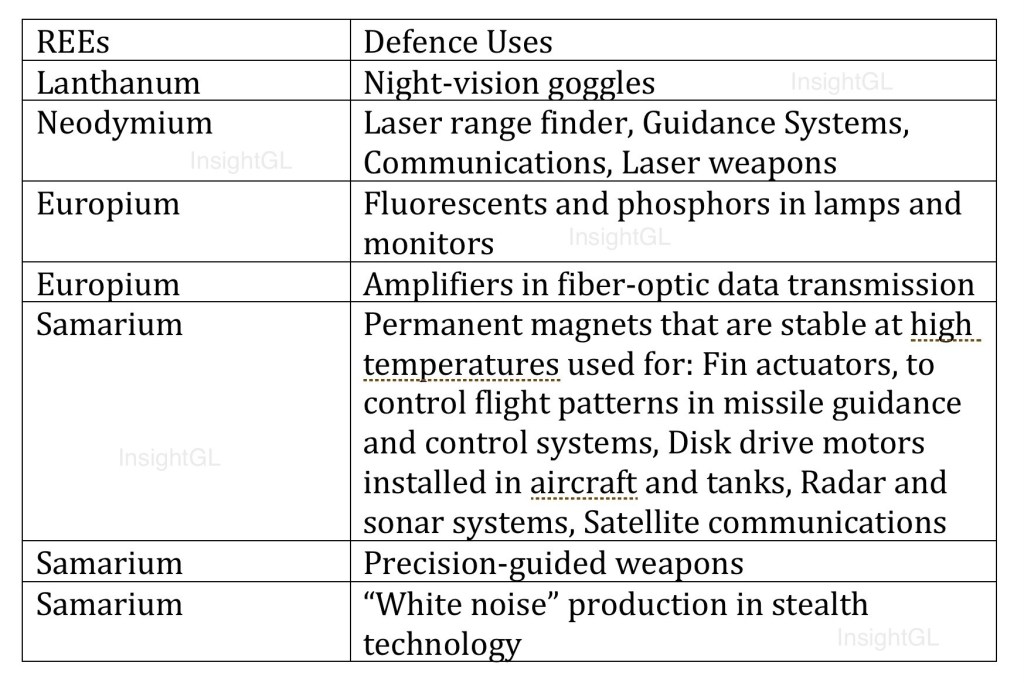

Why can’t we live without rare-earth elements? They are found in many everyday gadgets, as well as in nearly all high-tech devices. Among their numerous benefits, rare-earth batteries are environmentally friendly, provide higher energy density, and have better discharge characteristics. High-strength rare-earth magnets have enabled the miniaturization of audio and video equipment, computers, vehicles, communication systems, and military gear. Additionally, the rare-earth element erbium is used to amplify signals in fiber-optic cables, allowing for long-distance signal transmission. The defense industry significantly relies on rare-earth elements (REEs). Some of their applications include:

Where Do We Stand Today

Rare-earth elements are often called the new gold or oil because of their vital role in technological advancements. They are essential for various applications, including satellites, computers, and modern military hardware. For instance, advanced aircraft like the F-35 utilize over 400 kilograms of rare-earth materials.

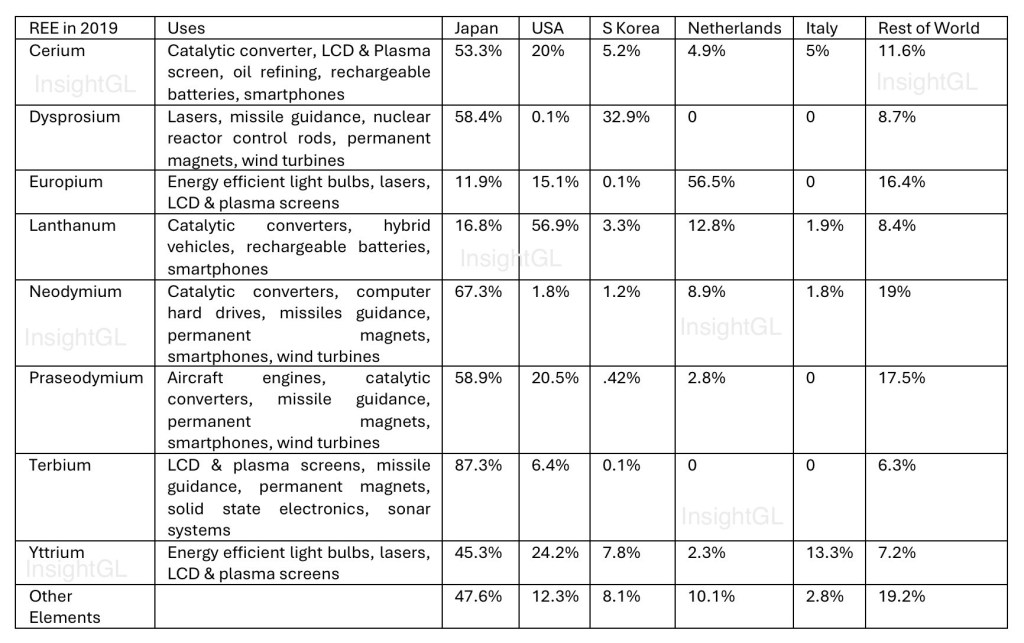

In 2019, Japan was the largest importer of Chinese rare-earth elements, accounting for 36% of imports. The United States closely followed at 33.4%, with the Netherlands at 9.6%, South Korea at 5.4%, and Italy at 3.5%. The most significant export by volume from China that year was lanthanum, which is used in hybrid vehicles and represented 42.6% of exports. However, terbium, used in solid-state electronic devices, television screens, and sonar systems, was the top earner due to its higher market value.

Although China holds less than 36% of the world’s rare-earth reserves, it currently controls about 90% of global production through territorial control and exclusive mining rights. Furthermore, China faces fewer environmental and labor regulations, which reduces the costs associated with mining and manufacturing rare-earth elements. From 2008 to 2018, China accounted for 42.3% of the world’s rare-earth exports, while the United States was a distant second at 9.3%. Malaysia, Austria, and Japan were also among the top five exporting countries.

In 2024, worldwide rare-earth imports totaled just $3.74 billion, a minuscule amount compared to over $2.6 trillion in global crude oil imports. However, the estimated total value of industries that rely on these minerals is remarkable. For example, in 2024, Apple Inc. reported a turnover of $391.04 billion, heavily dependent on rare-earth elements for manufacturing.

How Did China Reach Here

Throughout the 20th century, the United States was largely self-sufficient, meeting all of its rare earth element (REE) needs domestically. However, this situation began to shift in the 1990s and took a drastic turn in the 2000s. From 2020 to 2023, the United States imported 70 percent of its rare earth compounds and metals from China. Other significant sources included Malaysia (13%), Japan (6%), and Estonia (5%), with the remaining 6% coming from various other countries. Various factors related to China’s rise were:

– Free trade agreements with the United States

– Lower labor costs

– Lax regulatory and pollution requirements

– Exploitation of rare earth resources to expand electronics manufacturing

– Taking advantage of vulnerabilities in poorer countries

– Closing of US plants due to regulatory demands

China has exploited cash-strapped African nations by using an age-old barter system to gain mining rights. For example, the Democratic Republic of the Congo has awarded rights to China for its lithium, cobalt, and coltan mines in exchange for the construction of urban roads, highways, and hospitals. Similarly, Kenya granted mining rights to China in exchange for a $666 million data center. Other countries, such as Angola, Cameroon, Tanzania, and Zambia have also been targeted for REE extraction, particularly Tanzania, which has significant deposits of neodymium and praseodymium, key components in precision-guided munitions technology.

China is employing similar tactics in Latin America and the Caribbean. Following the discovery of an $8.4 billion rare earth deposit in Brazil, China has become the country’s undisputed top trade partner.

The largest exploitation by China is currently taking place in Myanmar. In Kachin State, an environmental catastrophe is unfolding as massive excavators dig for valuable rare earth elements, leaving behind toxic pools and barren landscapes. This damage is part of China’s strategy to dominate the global supply of critical minerals, capitalizing on Myanmar’s political isolation.

China’s rare earth extraction in Myanmar has surged, with imports increasing by 70% in the first half of 2023, totaling over 34,000 metric tons. This stockpiling seems to be a preparation for potential future sanctions.

The once-pristine Kachin region now resembles a devastated landscape due to over a 40% increase in operations by Chinese companies utilizing local proxies. Myanmar has emerged as a key source for heavy rare earths, supplying around 40% of essential elements like dysprosium, yttrium, and terbium.

Japan Show the Way

Japan has important lessons from its past. In 2010, China temporarily banned rare earth exports to Japan due to a territorial dispute over the Senkaku Islands. This crisis prompted Japan to reevaluate its supply chain security. Currently, Japan is actively working to strengthen its supply chain resilience, especially in response to recent export bans by China on rare earth elements that are vital for the automotive, robotics, and defense industries. This situation highlights Japan’s experience and the importance of supply chain security.

In response to these challenges, Japan has begun stockpiling rare earth elements, focusing on recycling, and investing in alternative technologies and projects outside of China, such as Australia’s Lynas. This effort has significantly reduced Japan’s dependence on Chinese rare earths from over 90% in 2010 to below 60% currently. Japan aims to decrease this reliance to below 50% within the year.

China’s recent restrictions are closely linked to U.S. tariffs on Chinese goods, raising concerns in the Western auto industry about potential production disruptions. Europe also faces limitations in its domestic production of rare earths and, like the U.S., relies heavily on imports, particularly from China. However, plans are underway in Europe to develop domestic resources and processing capabilities for rare earth elements.

The Indian Story

Global reserves of rare earth elements (REEs) are estimated at 120 million metric tons based on a rare-earth-oxide (REO) basis. The countries with the largest reserves, in decreasing order, are China, Brazil, India, Australia, Russia, and Vietnam. This highlights that India possesses the third-largest reserves of rare earth elements in the world; however, it primarily imports finished REE products from China, which is an unreliable source.

India recognized the significance of rare earth elements as early as 1950 and established Indian Rare Earths Limited to begin extracting these resources. Unfortunately, this model eventually collapsed, leaving imports as the only viable option. The challenge lies in the fact that while having deposits of REEs is one aspect, safely and efficiently exploiting them is another. Mining and extraction require substantial capital investment, energy, and can release toxic by-products. In India, REEs are primarily produced from monazite found in heavy mineral sands. Significant rare earth minerals located in the country include ilmenite, rutile, zircon, garnet, monazite, and sillimanite, collectively termed Beach Sand Minerals.

Currently, the two government-owned producers in India are the Rare Earth Division of Indian Rare Earths Ltd. (IREL), with a capacity of 6,000 MT per year, and Kerala Minerals and Metals Ltd. (KMML), with a capacity of 240 MT per year. Additionally, three other companies—National Aluminum, Hindustan Copper, and Mineral Exploration Corporation—plan to explore mines in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, and other countries to build strategic reserves of tungsten, nickel, and rare earths.

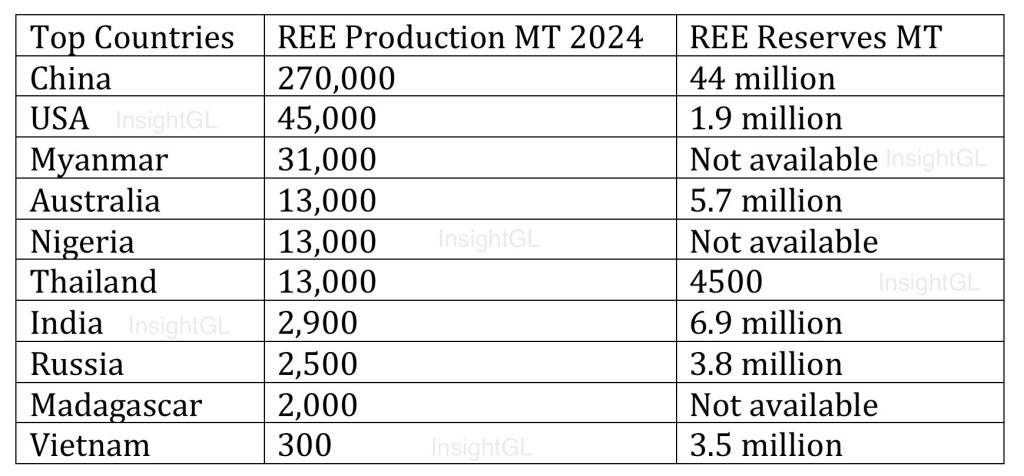

India’s estimated reserves of REEs have been revised from 3.1 million MT to 6.9 million MT. In 2014, Indian Rare Earths and Toyota Tsusho Exploration signed an agreement to explore and produce rare earths through deep-sea mining. However, despite this partnership, India’s current production of rare earths remains significantly lower than its potential. The country holds approximately 35 percent of the world’s total beach sand mineral deposits, which are substantial sources of rare earths. In 2024, India’s production of rare earths was merely 2,900 MT, an increase from 1,800 MT in 2018. In contrast, China produced 270,000 MT, the US 45,000 MT, Myanmar 31,000 MT, and Australia 13,000 MT.

Conclusion

To address energy security risks associated with rare earth elements (REEs), countries like India need to adopt a three-pronged approach: focusing on recycling, exploring alternative import sources, and investing in research and development (R&D). Each of these strategies has its challenges; recycling is energy-intensive and requires a well-organized supply chain, R&D can be expensive and unpredictable, and alternative imports are often limited by geopolitical factors.

India is actively pursuing all three strategies. The Ministry of Mines has launched a Production Linked Incentives scheme to promote the recycling of critical minerals. The recent removal of IREL (Indian Rare Earths Limited) from the U.S. export control list is expected to strengthen India’s REE supply chain. Additionally, IREL has established a Rare Earth Permanent Magnet Plant in Visakhapatnam with an annual production capacity of 3,000 kg.

The India-Central Asia Rare Earths Forum (ICAREF) is also working on joint mining ventures to create a regional REE market. Despite challenges such as geographic barriers and limited extraction technologies, the forum aims to facilitate a transition to renewable energy and reduce reliance on exports from China.

Further to this, on June 6, 2025, India and five Central Asian countries expressed interest in jointly exploring rare earth and critical minerals. This initiative is part of New Delhi’s efforts to decrease dependence on shipments from China, which has restricted the export of rare earth materials. This discussion took place during the fourth meeting of the India-Central Asia Dialogue, as stated by the Ministry of External Affairs.

Today, rare earth elements (REEs) are essential to modern life. Dependence on China for REEs and other critical resources has created challenges for India and the rest of the world. China is likely to continue using its control over the supply chain as a leverage point. It is crucial for the global community to recognize this reality, innovate, and establish new alliances.

Leave a reply to rks Cancel reply