For over a week, there has been a comparison across social media between the startup ecosystems of India and China. Shortly after, during the second ‘Startup Maha Kumbh’ event in Delhi, India’s Union Commerce Minister Piyush Goyal repeated the same points verbatim. It’s unclear whether the meme influenced the minister or vice versa. While comparisons can be useful for learning and improvement, I believe this particular comparison was biased.

The meme:

If we examine the columns under India and China, it becomes evident that the comparison should be made within the same category, rather than across random categories. This prompted me to conduct a factual study to highlight, what India has achieved, where we fall short, and what can be done to improve in those areas.

First, let us look at the startup ecosystem in both countries:

Funding and other data:

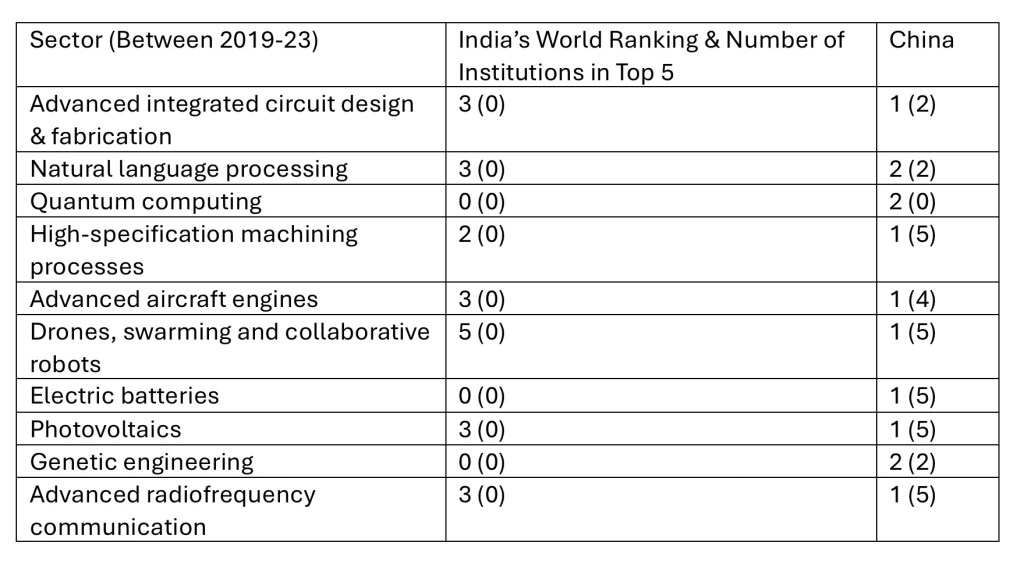

The data clearly illustrates India’s position within the startup ecosystem. To keep it accessible for the average reader, I will summarize the key findings. The Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) assessed 64 critical technologies and important fields, including defense, space, energy, the environment, artificial intelligence (AI), biotechnology, robotics, cybersecurity, computing, advanced materials, and vital quantum technologies. Below is an overview comparing India and China regarding 10 of these 64 technologies:

From 2003 to 2007, the United States led in 60 out of the 64 technologies. However, in the most recent five-year period from 2019 to 2023, it has only maintained a lead in seven technologies. Conversely, while China held the lead in just three technologies between 2003 and 2007, it has now become the dominant nation in 57 out of 64 technologies from 2019 to 2023. At that time, India was ranked among the top five countries in only four technologies, but today it ranks in the top five for 45 out of 64 technologies and has surpassed the U.S. in two new fields—biological manufacturing and distributed ledgers—now holding the second position in seven technologies overall.

However, it’s essential to temper our excitement with the realization that, at times, the gap between the top-ranking countries (China or the U.S.) and India (in third place) can be as significant as 30-40%. Unfortunately, despite India’s upward trajectory, few Indian institutions have appeared in the top five rankings over the years from 2003 to 2023. Only five Indian institutions are currently ranked among the top five across the 64 technologies, indicating that India’s research and scientific expertise in critical technologies remains fragmented.

This lack of prominent institutional performers may hinder India’s ability to attract foreign research talent and discourage distinguished Indian scientists and technologists from staying at or returning to Indian institutions. In contrast, Singapore—despite breaking into the top five rankings in only two technologies (supercapacitors and novel metamaterials)—is well-represented in institutional rankings, with Nanyang Technological University appearing in the top five for three technologies and the National University of Singapore for two.

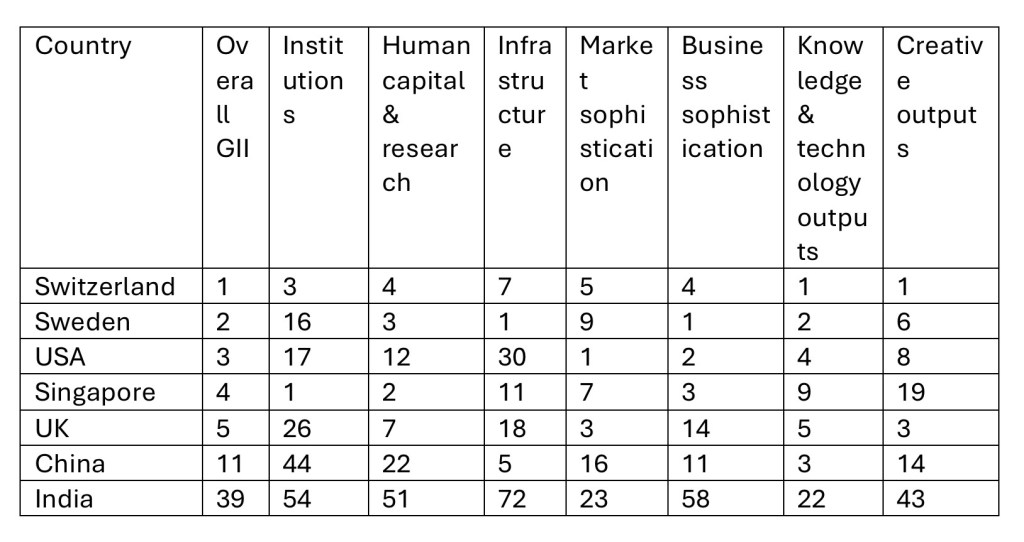

Global Innovation Index (GII) 2024

While ASPI gives access to specialized patent information, World Intellectual Property Organization, a UN agency, focuses on intellectual property (IP), thus giving a much broader perspective. The WIPO index provides a comprehensive analysis of the current state of global innovation, revealing a complex landscape subject to economic, geopolitical and technological factors. Findings serve to highlight progress, as well as challenges across four key stages of the innovation cycle: science and innovation investment, technological progress, technology adoption, and the socioeconomic impact of innovation.

Top S&T cluster by economy or cross-border region:

A common characteristic of top-performing nations is the existence of thriving science and technology (S&T) clusters. These clusters, which can encompass entire regions or cities, form the foundation of a strong national innovation ecosystem. Unfortunately, despite its reputation as India’s innovation hub, Bangalore only ranks 56th.

Economies with three or more clusters among top 100 S&T clusters:

The top global R&D spenders (PPP):

It has been observed that countries with high private R&D investment tend to be more successful than those where public R&D spending dominates. Israel stands out, with the private sector contributing 92% of total R&D, followed by Vietnam (90%), Ireland (80%), and both Japan and South Korea (79%). The private sector also plays a significant role in the United States, China, several European economies, Thailand, Singapore, Turkey, Canada, Australia, the United Arab Emirates, and others, where it accounts for over 50% of total R&D.

India’s overall R&D spending is inadequate, and the larger concern is the low participation of the private sector in research and development. In India, public R&D accounts for 63.55% of the total, while private R&D constitutes only 36.45%.

Conclusion:

India has considerable potential due to its large population, open economy, and cost efficiency in business. As a leader in technology services, India has experienced notable startup growth, driven by its vast domestic market. However, brain drain remains a challenge, as top talent often seeks opportunities abroad due to limited high-paying jobs and infrastructure issues.

While China excels in cash-intensive hardware, India is plucking low-hanging fruits in software and enterprise technology. With 65% of its population under the age of 35, India has a demographic advantage, but this can only be fully realized by building a skilled workforce.

China has made significant progress by leveraging government support, substantial investments in deep technology, and its vast domestic market. In contrast, India has encountered several challenges, including a shortage of capital, regulatory obstacles, and an emphasis on consumer-oriented applications. Furthermore, the absence of world-class institutions, widespread corruption in various departments, and a lack of R&D funding and risk-taking willingness among the private sector are barriers to India’s potential success.

It is the minister’s responsibility to take a proactive role in addressing the challenges faced by startups, rather than merely delivering a lecture and departing. Additionally, industry leaders should support startups that operate in critical areas, which often either get acquired by foreign entities at the first opportunity or shut down due to a lack of funding. As a nation, India has significant differences with China on a military level. However, now is the time to learn from China’s approach to nurturing its startup ecosystem, even if we consider them an adversary.

References:

inc42.com/features/indian-startups-ecosystem-2024-review-charts-visuals

startupblink.com/startup-ecosystem/china

startupblink.com/startup-ecosystem/india

tractiontechnology.com/blog/navigating-chinas-dynamic-startup-landscape-five-to-watch-in-2024

pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=2043805

aspi.org.au/report/aspis-two-decade-critical-technology-tracker

wipo.int/web-publications/global-innovation-index-2024/en/gii-2024-results.html

wipo.int/web/global-innovation-index/w/blogs/2024/end-of-year-edition

Leave a reply to Emmanuel Prasad Cancel reply